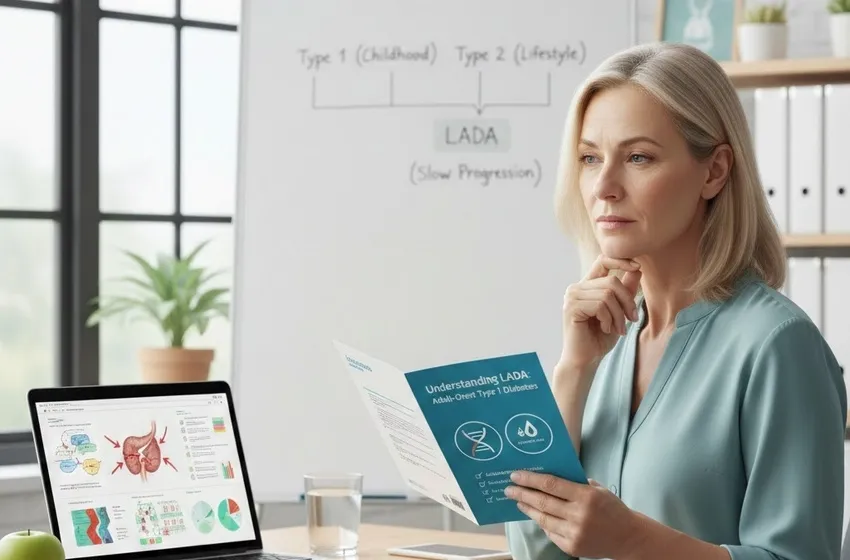

Learn the signs of adult-onset Type 1, the role of genetic risk, and why autoimmune testing is vital to avoid misdiagnosis.

Why Are People Getting Type 1 Later in Life? Understanding LADA

For decades, the medical community and the general public operated under a simple, binary view of diabetes: Type 1 was a "juvenile" disease discovered in childhood, and Type 2 was an "adult-onset" disease caused by lifestyle and insulin resistance. However, a growing body of research is dismantling this stereotype. We are now seeing a significant rise in adult-onset Type 1 cases, specifically a form known as LADA diabetes (Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults).

LADA is often referred to as "Type 1.5" because it sits in the murky middle ground between the two classic types. It is an autoimmune condition like Type 1, but it manifests in adulthood and progresses with a deceptively slow progression that mimics Type 2. Understanding why this happens and why LADA is so frequently misunderstood is critical for the millions of adults currently navigating a confusing diagnosis.

What is LADA? The "Hidden" Autoimmune Diabetes

LADA occurs when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, similar to classic Type 1 diabetes. However, unlike the childhood version where the "honeymoon phase" is short and insulin dependence is immediate, LADA develops much more gradually.

The Three Diagnostic Criteria for LADA:

- Age of Onset: Typically occurs in adults over the age of 30.

- Autoimmune Testing: The presence of at least one lung or islet-related autoantibody (most commonly GADA).

- Insulin Independence: The patient does not require insulin therapy for at least the first six months after diagnosis.

The Misdiagnosis Trap: Why LADA is Often Mistaken for Type 2

The most significant challenge for patients is the high rate of misdiagnosis. Statistics suggest that up to 10% of people diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes actually have LADA. Because a patient is older (e.g., 45 years old) and may be slightly overweight, many primary care physicians default to a Type 2 diagnosis without further investigation.

Why the confusion happens:

- Initial Response to Oral Meds: In the early stages, the pancreas still produces some insulin. Consequently, patients with LADA often see an initial improvement in blood sugar when taking Type 2 medications like Metformin. This "false positive" response reinforces the wrong diagnosis.

- The Weight Factor: While many LADA patients are lean, the rising rates of global obesity mean that an adult can have both the genetic risk for autoimmunity and the metabolic markers of Type 2.

- Slow Progression: Unlike the sudden "crash" into Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) seen in children, LADA can simmer for years. The slow decline in beta-cell function masks the autoimmune nature of the disease.

Key Insight: If you have been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes but find that your blood sugar remains high despite strict diet, exercise, and multiple oral medications, you should advocate for autoimmune testing.

The Role of Genetics and Environment: Why Now?

Why are we seeing more cases of adult-onset Type 1 today? Researchers are looking at the intersection of genetic risk and environmental triggers.

Genetic Susceptibility

While childhood Type 1 is heavily linked to specific high-risk HLA gene variants, LADA patients often carry a mix of genes. They may have "protective" versions of the HLA genes that delay the onset of the autoimmune attack until later in life, or they may possess a combination of Type 1 and Type 2 genetic markers.

Environmental Triggers

The "hygiene hypothesis" and changes in the modern gut microbiome are also under scrutiny. Factors like viral infections, chronic stress, or even late-life changes in the immune system might trigger a dormant genetic predisposition, causing the immune system to finally turn on the pancreas in middle age.

The Importance of Autoimmune Testing

The only way to definitively distinguish LADA from Type 2 is through specialized blood work. Standard glucose and A1c tests cannot tell the difference.

1. Autoantibody Panels The most common test for LADA is the GAD (Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase) antibody test. Other markers include:

- IA-2A (Insulinoma-Associated-2 Autoantibodies)

- ZnT8W (Zinc Transporter 8)

- ICA (Islet Cell Antibodies)

2. C-Peptide Test This test measures how much insulin your body is currently producing. In Type 2, C-peptide levels are often high (indicating insulin resistance). In LADA, C-peptide levels are typically low or "low-normal" and continue to drop over time as the slow progression of the autoimmune attack continues.

Moving Toward the Right Treatment

A correct diagnosis changes everything. While a Type 2 patient might be told to "work harder" on their diet, a LADA patient needs to understand that their beta cells are being destroyed by an immune process they cannot control. Early identification allows for:

- Preservation of Beta Cells: Starting low-dose insulin earlier may help "rest" the remaining pancreatic cells and delay full dependence.

- Prevention of DKA: Knowing you have an autoimmune condition means you can monitor for ketones, reducing the risk of a life-threatening emergency.

- Reduced Psychological Burden: Many LADA patients feel like they have "failed" at managing Type 2, when in reality, they were fighting an un-diagnosed autoimmune battle.

Conclusion

The rise of LADA diabetes reminds us that diabetes exists on a spectrum. Getting adult-onset Type 1 is not a result of lifestyle failure; it is a complex intersection of genetic risk and a late-acting immune response. By prioritizing autoimmune testing and recognizing the signs of slow progression, we can move past the era of misdiagnosis and ensure every adult receives the specific care their body requires.