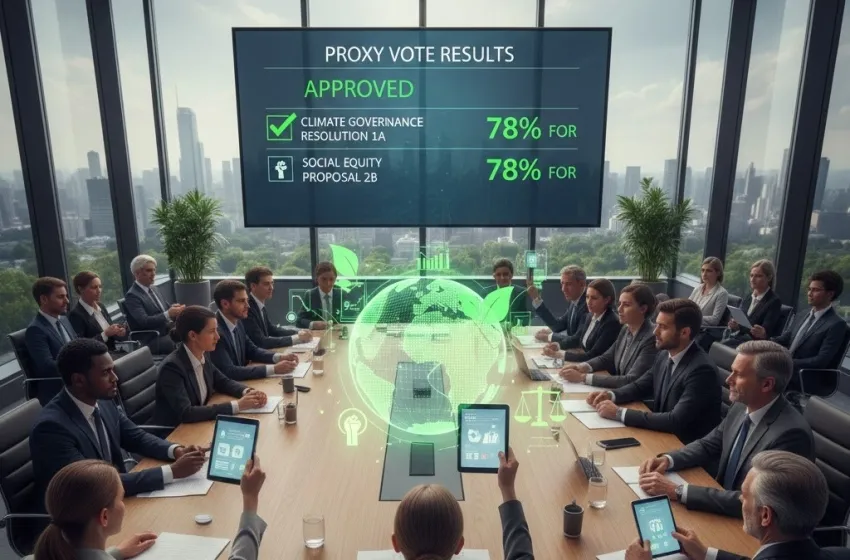

Learn how large asset managers use shareholder proposals to force ESG disclosure.

The Power Shift: Investor Activism Driving Climate and Social Governance

The financial landscape is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the ascendancy of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria. At the core of this change is investor activism, where shareholders actively leverage their ownership rights to influence corporate direction on matters of sustainability and social responsibility. Once a niche concern focused primarily on executive pay and financial maneuvers, this form of corporate influence has decisively pivoted toward systemic issues like climate governance and social equity. This comprehensive analysis delves into the mechanisms, impact, and future of this powerful trend, examining how both institutional giants and determined small owners are utilizing proxy voting to effect meaningful change.

The Evolution of Shareholder Engagement

The surge in ESG-focused investor activism is not accidental; it is a direct response to the growing recognition that environmental and social risks—from climate change to inequality—pose material financial threats to long-term value creation.

Historically, shareholder proposals often focused on traditional governance topics like board structure and executive compensation. However, the early 21st century has seen a dramatic shift. The number of climate-related shareholder proposals and social resolutions has escalated, moving from requests for basic ESG disclosure to demands for specific, measurable, and time-bound corporate action.

A significant driver of this shift is the massive growth of assets committed to responsible investing. The United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) network, for example, has grown to include over 3,000 signatories representing more than $100 trillion in assets under management (AUM) as of 2020. This indicates that a substantial portion of global capital is now formally guided by ESG considerations, making investor engagement a central fiduciary duty.

Key Mechanisms of Corporate Influence

Shareholders have a potent arsenal of tools to exert corporate influence, most notably through the annual general meeting (AGM) process.

1. Shareholder Proposals and Social Resolutions

Shareholder proposals are formal requests placed on the company's proxy ballot by investors, typically asking management or the board to take a specific action or disclose certain information. These proposals are the primary vehicle for driving change on environmental and social issues.

Climate Proposals: Early climate proposals often requested ESG disclosure, such as reporting on Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. More recent, sophisticated proposals demand alignment with the Paris Agreement, setting net-zero targets, or disclosing how capital expenditure aligns with a 1.5°C scenario. For instance, after years of pressure, in May 2017, the shareholders of ExxonMobil voted for a comprehensive assessment of risks related to climate change. As of 2024, approximately 95% of S&P 500 companies disclose their Scope 1 and 2 emissions, and over 87% have established quantitative GHG reduction targets, showing a clear, measurable impact from shareholder pressure.

Social Resolutions: These proposals focus on the 'S' in ESG, including issues such as racial and gender diversity on boards, human rights in the supply chain, worker pay, and political spending. While less numerous than climate proposals in some years, they have garnered significant attention, particularly following major social movements.

2. Proxy Voting

Proxy voting is the decisive mechanism. Even non-binding proposals—those that do not legally compel the company to act—can be highly influential. A high vote for a social resolution or a shareholder proposal signals strong investor dissent and puts immense pressure on the board of directors.

How Large Asset Managers and Minority Shareholders are Using Their Voting Power

The power dynamics in modern investor activism are dual-layered: the immense, concentrated influence of major financial institutions, and the persistent, strategic efforts of smaller, dedicated minority shareholders.

The Giant's Stride: Large Asset Managers

Firms like BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street—often referred to as the "Big Three"—are among the largest asset managers globally, collectively managing trillions of dollars. Their sheer size means they hold significant, often deciding, stakes in nearly every major publicly traded company. When these institutions engage in proxy voting, their decisions can swing the outcome of any shareholder proposal.

Large asset managers leverage their size in several ways:

- Direct Engagement: The preferred method is often "quiet diplomacy"—private dialogue with corporate boards and executives. The threat of a negative vote on a proposal or on a director's re-election is a powerful lever. An example of effective engagement is when activist funds successfully induce ESG rating adjustments; firms with poor pre-existing ESG ratings often experience a ratings increase after complying with activist demands.

- Supporting Key Resolutions: When dialogue fails, their support for a shareholder proposal can push it to a majority or near-majority vote, forcing the board to take the matter seriously.

- Voting Against Management: A critical, and increasingly common, tactic is voting against the re-election of directors, particularly those responsible for climate or social risk oversight, or against management pay packages, as a direct expression of dissatisfaction with the company's lack of progress on ESG issues.

However, the role of these massive institutions is often scrutinized. While they have dramatically ramped up their climate and social engagement, recent analysis indicates fluctuating support for activist resolutions. For example, some reports showed that the average support for environmental and social shareholder resolutions in 2024 hit a low, with major asset managers often voting against proposals. This highlights the tension between fiduciary duty, which some interpret as strictly maximizing short-term financial returns, and the push for long-term sustainability.

The Strategic Pressure: Minority Shareholders

While they lack the colossal voting bloc of the large asset managers, minority shareholders—including faith-based investors, pension funds, and dedicated socially responsible investment (SRI) funds—play a crucial role as the engine of investor activism.

- Proposal Submission: These investors are often the original filers of climate and social resolutions. They use the right to file shareholder proposals (governed by rules like the SEC's Rule 14a-8 in the U.S.) to force a public debate on critical issues.

- Raising Awareness: They bring novel and ambitious issues to the corporate agenda, often years before they become mainstream. Their proposals serve as a constant pressure point, ensuring that topics like Scope 3 emissions, racial equity audits, and political lobbying transparency are continually addressed.

- Coalition Building: Minority shareholders frequently form alliances to amplify their influence. Organizations like Ceres and the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility (ICCR) coordinate efforts, allowing smaller stakes to collectively achieve a significant voting percentage.

The persistent pressure from these groups has forced companies to enhance ESG disclosure, even in the absence of mandatory regulation. Studies confirm that environmental shareholder activism is particularly effective at increasing the voluntary disclosure of climate risk information, especially when initiated by long-term, legitimacy-driven institutional investors. Companies that subsequently disclose this information often achieve a higher valuation, suggesting the market explicitly values this transparency.

The Impact on Climate Governance and Social Policy

The ultimate goal of investor activism is to compel genuine change in corporate strategy. This activism has yielded tangible results across the E and S spectrums.

Climate Governance

In climate governance, shareholder pressure has directly influenced the adoption of decarbonization strategies:

- Net-Zero Commitments: Following years of resolutions and engagement, numerous high-emitting companies have adopted formal net-zero emissions targets.

- Say-on-Climate: Some companies have proactively adopted "Say-on-Climate" votes, allowing shareholders to vote on the company's climate transition plan, a direct result of investor demands for greater oversight.

- Stranded Asset Risk: Activism has forced energy companies to account for the financial risk of stranded assets—fossil fuel reserves that may become uneconomic or unusable due to stricter climate regulations.

Social Resolutions and Policy

On the social front, activism has pushed for structural change:

- Board Diversity: Social resolutions focused on board diversity have driven significant, measurable changes. Data from major indices show a steady increase in the representation of women and people of color on corporate boards.

- Human Capital Management: Proposals related to labor practices, pay equity, and worker safety, particularly in supply chains, have gained traction, forcing companies to address the 'S' as a material risk.

- Racial Equity Audits: A new wave of proposals is demanding independent racial equity audits, pushing companies to assess and mitigate the adverse impacts of their policies and practices on communities of color.

Conclusion

Investor activism is no longer a peripheral corporate concern; it is a fundamental pillar of modern climate governance and social accountability. Large asset managers and minority shareholders alike are expertly deploying proxy voting and shareholder proposals to translate ESG principles into concrete, mandatory business strategy.

The demand for enhanced ESG disclosure is rising, driven by the belief that transparency is a prerequisite for long-term value. As global environmental and social challenges intensify, the leveraging of ownership rights to exert corporate influence will only grow, solidifying investor activism as one of the most powerful external forces driving corporate change toward a more sustainable and equitable future.