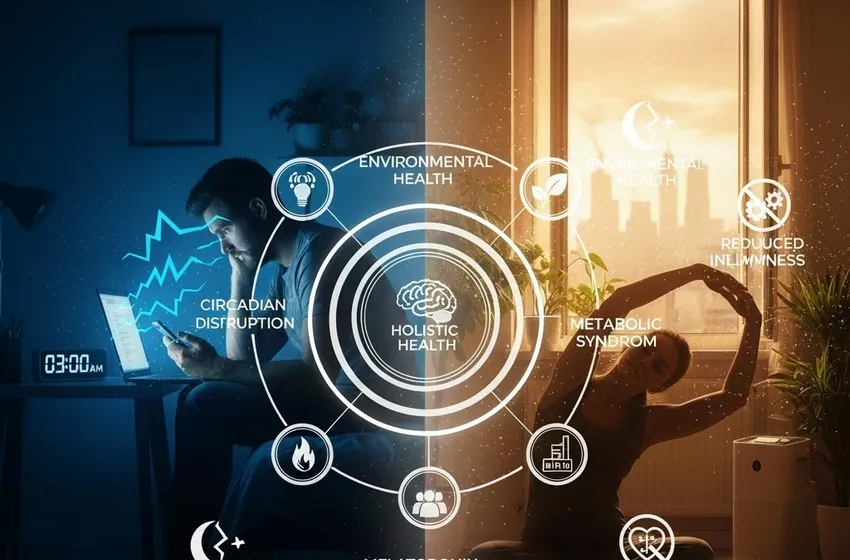

Learn how sleep metabolism affects chronic disease risk and environmental health.

The Hidden Pulse of Modern Life: The Impact of Blue Light and Environmental Factors on Health

In the span of a single century, human environments have shifted more radically than in the previous ten thousand years. We have traded the rhythmic cycles of the sun for the persistent glow of LEDs and exchanged pristine wilderness for urban landscapes saturated with invisible stressors. Today, understanding the intersection of environmental health and modern technology is no longer a niche scientific pursuit—it is a fundamental requirement for longevity.

The most pervasive of these modern shifts is our relationship with light. While we often think of light simply as a tool for vision, it is actually a powerful biological signal. Specifically, the rise of blue light exposure and the accumulation of pollution impact are fundamentally altering our internal chemistry, leading to a cascade of physiological changes.

The Science of Light: Why Blue Light Matters

To explain blue light exposure, we must first look at the electromagnetic spectrum. Blue light is a high-energy visible (HEV) light with short wavelengths. While its primary natural source is the sun—which helps us stay alert and focused during the day—our modern environment is flooded with artificial versions from smartphones, laptops, and energy-efficient lighting.

The Mechanism of Circadian Disruption

Our bodies operate on an internal 24-hour clock known as the circadian rhythm. This rhythm is regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain, which responds directly to light cues. When blue light hits the melanopsin-containing cells in our retinas, it signals the brain to suppress melatonin, the hormone responsible for sleep.

While this suppression is beneficial at 10:00 AM, it is catastrophic at 10:00 PM. This mismatch leads to circadian disruption, a state where our internal biological timing is out of sync with the external environment. This "social jetlag" doesn't just make us tired; it triggers a systemic breakdown in cellular repair.

Beyond Sleep: The Environmental Health Crisis

While light is a "visual pollutant," it exists alongside more tangible environmental stressors. Environmental health encompasses the physical, chemical, and biological factors external to a person. In our current era, the pollution impact from particulate matter (PM2.5), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and endocrine disruptors creates a "toxic load" that the human body was not evolved to handle.

The Synergy of Light and Pollution

Emerging research suggests that environmental factors do not act in isolation. For instance, poor air quality can exacerbate the inflammatory response already triggered by poor sleep. When we combine the oxidative stress caused by urban pollution with the systemic inflammation caused by lack of rest, we see a rapid increase in chronic disease risk.

Sleep Metabolism: The Internal Economy

One of the most critical, yet overlooked, consequences of these environmental shifts is the effect on sleep metabolism. Sleep is not a passive state of rest; it is an active period of metabolic regulation.

- Insulin Sensitivity: Sleep deprivation and late-night blue light exposure can reduce insulin sensitivity after just one night, mimicking the blood sugar profiles of pre-diabetics.

- Ghrelin and Leptin: Circadian disruption upsets the balance of hunger hormones. Ghrelin (the "hunger" hormone) increases, while Leptin (the "fullness" hormone) decreases, leading to cravings for high-calorie, sugary foods.

- Lipid Processing: The body’s ability to process fats is tied to the liver’s circadian clock. When we disrupt this clock with artificial light, we alter how the body stores and burns fat.

The Long-Term Cost: Chronic Disease Risk

The cumulative effect of blue light exposure, poor air quality, and disrupted rhythms is a significant elevation in chronic disease risk. We are seeing a global rise in "lifestyle diseases" that are, in many ways, "environmental diseases."

- Cardiovascular Health: Chronic exposure to nighttime light and noise pollution increases cortisol and adrenaline. Over time, this leads to hypertension and arterial stiffness.

- Neurological Decline: During deep sleep, the brain’s glymphatic system flushes out neurotoxic waste, such as beta-amyloid plaques. By disrupting sleep through environmental factors, we potentially increase the risk of neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s.

- Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: The link between sleep metabolism and weight gain is undeniable. Populations living in highly lit urban areas with high pollution impact show higher rates of Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

Mitigating the Impact: Strategies for Modern Living

We cannot entirely escape the modern world, but we can optimize our interaction with it. Protecting your environmental health requires a multi-faceted approach.

Digital Hygiene and Light Management

- The 2-Hour Rule: Eliminate blue light exposure at least two hours before bed.

- Morning Sunlight: View natural sunlight within 30 minutes of waking to anchor your circadian rhythm.

- Blue-Blocking Glasses: Amber-tinted glasses can reduce melatonin suppression if you must work late.

Improving Your Immediate Environment

- Air Filtration: Use HEPA filters to reduce the pollution impact inside your home.

- Thermal Regulation: A cooler room (around 18°C or 65°F) supports better sleep metabolism.

- Blackout Curtains: Eliminate light creep from streetlamps to prevent micro-disruptions.

| Environmental Factor | Health Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Blue Light | Melatonin suppression | Blue-light filters, morning sun |

| Air Pollution | Systemic inflammation | HEPA air purifiers, indoor plants |

| Noise Pollution | Cortisol spikes | White noise machines, earplugs |

| Temperature | Poor sleep quality | Cooling mattress pads, ventilation |

The Future of Environmental Health

As we look toward the future, the concept of "well-being" is expanding. It is no longer just about diet and exercise; it is about "circadian stewardship." To truly lower chronic disease risk, we must advocate for environments that respect our biological heritage. This means cleaner air, quieter streets, and a return to the natural darkness that our cells require for healing.

Conclusion

The interplay between blue light exposure, environmental health, and sleep metabolism defines the modern health landscape. While the pollution impact and artificial glow of our cities present new challenges, our understanding of circadian disruption provides a roadmap for recovery. By making conscious choices, we can protect ourselves from the rising tide of chronic illness.