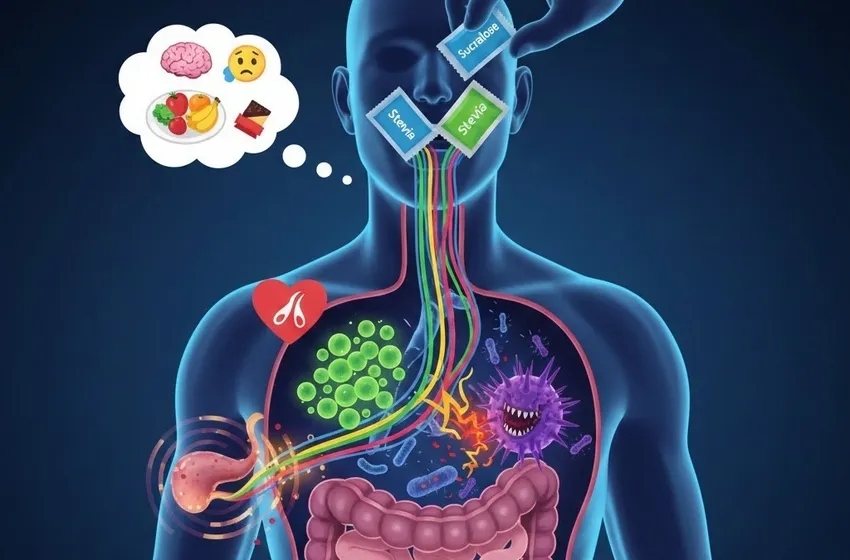

Discover how sugar substitutes impact glucose, insulin levels, and your gut microbiome.

The Metabolic Paradox: Beyond the Calorie Count

The original appeal of sugar substitutes was simple: they provide sweetness without the calories per gram found in sucrose. Because they aren't "sugar," the assumption was that they would have zero effect on blood sugar. However, the body is a complex system of receptors, not just a simple furnace for burning calories.

Research now suggests that the brain and the gut communicate via "sweet taste receptors" ($T1R2$ and $T1R3$) that exist not just on the tongue, but throughout the digestive tract. When these receptors are triggered by sugar substitutes, the body may prepare for a glucose load that never arrives, potentially leading to a glucose impact that is far from neutral.

Sucralose: A Modern Metabolic Question Mark

Sucralose (commonly known as Splenda) is one of the most widely consumed sweeteners globally. While it is hundreds of times sweeter than sugar and passes through the body largely undigested, recent human trials have raised red flags.

-

Insulin Sensitivity: New studies in 2024 and 2025 have shown that chronic consumption of sucralose may actually decrease insulin sensitivity. In some randomized controlled trials, participants consuming sucralose showed a higher insulin response when they eventually did eat actual sugar, compared to those who drank only water.

-

The Insulin Spike: Paradoxically, while sucralose itself doesn't contain glucose, it may prime the body to release more insulin. Over time, this "hyperinsulinemia" can contribute to the very metabolic syndrome it was intended to prevent.

Erythritol and the Controversial Research

Perhaps no sweetener has faced more controversial research recently than erythritol. As a sugar alcohol, it was long considered the "gold standard" for keto and low-carb diets because it has a high digestive tolerance and nearly zero calories.

However, landmark studies published in Nature Medicine and updated in 2024 by the Cleveland Clinic have linked high plasma levels of erythritol to an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks and strokes. The mechanism appears to be related to "platelet reactivity"—essentially, erythritol may make blood more prone to clotting. While the industry argues that high blood levels of erythritol can be produced naturally by the body (endogenous production), the association with dietary intake remains a significant point of concern for those with existing heart conditions.

The Microbiome Connection: A Hidden Battleground

One of the most profound shifts in our understanding of sugar substitutes involves the gut microbiome changes they may induce. Our gut is home to trillions of bacteria that play a critical role in how we harvest energy and regulate inflammation.

How Sweeteners Alter Your "Inner Garden"

Recent evidence suggests that certain sweeteners are not "invisible" to our gut bacteria. Instead, they can act as selective pressures, encouraging the growth of some microbes while inhibiting others.

-

Dysbiosis: Synthetic sweeteners like saccharin and sucralose have been shown to alter the composition of the gut microbiota. This state, known as dysbiosis, is often linked to increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut) and systemic inflammation.

-

Glucose Intolerance via Bacteria: In a famous 2022 study that continues to be cited in 2025, researchers found that the glucose impact of sweeteners was actually mediated by the gut. When the microbiome of "sweetener-consuming" humans was transplanted into germ-free mice, the mice developed glucose intolerance. This suggests that the sweeteners changed the bacteria, and the bacteria, in turn, changed the host’s metabolism.

Stevia: The "Natural" Exception?

Stevia, derived from the leaves of the Stevia rebaudiana plant, is often positioned as a safer, plant-based alternative.

-

Gut Health: Unlike its synthetic counterparts, stevia appears to be more "gut-neutral." Some studies even suggest it may have mild prebiotic effects, though more long-term human data is needed.

-

Metabolic Impact: Current research generally supports the idea that pure stevia does not raise blood glucose or insulin levels. However, many commercial stevia products are bulked with "fillers" like maltodextrin, which can cause a significant glucose impact.

Comparing Common Sweeteners

The table below summarizes the current scientific consensus (as of late 2025) on the three most discussed sweeteners.

| Sweetener | Source | Glucose/Insulin Impact | Gut Microbiome Effect | Key Concerns |

| Sucralose | Synthetic | May decrease insulin sensitivity | High potential for dysbiosis | Potential for "leaky gut" symptoms |

| Erythritol | Sugar Alcohol | Minimal to none | Generally neutral | Recent links to blood clotting/heart risk |

| Stevia | Plant-based | Low to neutral | Likely neutral/possibly beneficial | Aftertaste; purity of commercial blends |

The "Cephalic Phase" and Sweetness Confusion

A major theory discussed in the controversial research of 2025 is "sweetness-calorie decoupling." When we taste something sweet, our brain expects energy. When that energy doesn't arrive, it may lead to:

-

Increased Hunger: The brain continues to signal for food to find the calories it was promised.

-

Altered Dopamine Response: Frequent use of high-intensity sweeteners may "numb" the reward system, making naturally sweet foods like fruit taste bland and driving cravings for ultra-processed snacks.

Conclusion: A Cautious Approach

The "truth" about artificial sweeteners is that they are not the metabolic "free lunch" we once thought. While they remain a useful tool for short-term sugar reduction—especially for those with poorly controlled diabetes—the long-term gut microbiome changes and glucose impact suggest we should treat them with caution.

The current scientific debate highlights a "precision nutrition" approach: what works for one person’s microbiome may cause metabolic chaos for another. Until more definitive long-term human trials are completed, the safest path appears to be moderation and a preference for whole, minimally processed foods.