A guide on hypoglycemia treatment, using a glucagon pen, and building confidence with an emergency kit.

Navigating the World with Low Blood Sugar: A Guide to Managing Hypoglycemia in Public

Living with a condition that requires constant blood sugar monitoring—such as Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes—means that the world is your stage, but the script can change without warning. One of the most daunting challenges for anyone managing insulin-dependent diabetes is the threat of a "hypo" (hypoglycemia) while away from the safety and privacy of home.

This guide explores the practicalities, the emotional hurdles, and the vital importance of public awareness when dealing with low blood sugar in the real world.

The Reality of Public Hypoglycemia

Imagine you are at a crowded music festival, in the middle of a high-stakes job interview, or simply navigating a busy grocery store. Suddenly, the floor feels slightly unsteady. Your thoughts begin to fog. This is the onset of hypoglycemia, defined medically as blood sugar levels dropping below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).

Recognizing Low Blood Sugar Symptoms

The first step to safety is early detection. When you are in public, adrenaline and environmental distractions can mask the initial signs. Common low blood sugar symptoms include:

- Physical: Shaking, sweating, heart palpitations, and dizziness.

- Cognitive: Confusion, irritability, difficulty speaking, or "brain fog."

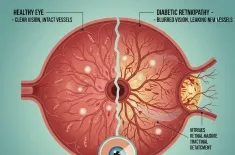

- Visual: Blurred or double vision.

In a public setting, these symptoms can unfortunately be misinterpreted by bystanders as intoxication or a lack of professionalism, which is why advocating for better public awareness is not just a social goal—it’s a safety requirement.

The Essentials: Your Portable Emergency Kit

You wouldn't leave home without your phone or keys; for someone prone to lows, an emergency kit is even more critical. This kit should be easily accessible—not buried at the bottom of a heavy backpack.

What’s Inside?

- Fast-Acting Glucose: Glucose tablets, gels, or a small bottle of juice. These are the gold standard for hypoglycemia treatment because they are measured and absorbed quickly.

- Backup Snacks: Complex carbohydrates (like crackers or a granola bar) to stabilize levels once the initial low is treated.

- Medical ID: A bracelet, necklace, or a digital ID on your phone’s lock screen that identifies you as having diabetes.

- The Glucagon Pen: For severe episodes where you may lose consciousness or be unable to swallow, a glucagon pen (or nasal glucagon) is a life-saving device that signals the liver to release stored glucose.

Step-by-Step: Managing a Hypo Event Outside

If you feel a low coming on while out and about, follow the Rule of 15:

- Stop and Sit: Do not try to "power through." Find a bench, sit on the floor, or lean against a wall.

- Test: If you have a Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) or a finger-prick meter, verify your level.

- Treat: Consume 15 grams of fast-acting carbs.

- Wait: Wait 15 minutes for the sugar to enter your bloodstream.

- Repeat: If you are still below 70 mg/dL, consume another 15 grams.

Advocating for Yourself

If you are alone in a store and feel a severe drop, speak up. Tell a staff member: "I have diabetes and my blood sugar is dangerously low. I need to sit here and drink this juice. Please stay with me for a moment." Most people are happy to help once they understand the situation.

Anxiety Management and the "Fear of Lows"

The psychological impact of public hypos is significant. Many people develop "hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure" or simply a deep-seated phobia of crashing in public. This can lead to keeping blood sugars intentionally high or social withdrawal.

Anxiety management is a core part of diabetes care. To regain your confidence:

- Trust your Tech: Use CGM alerts to catch drops before they become emergencies.

- Rehearse: Practice what you would say to a stranger or a coworker in a low-stress environment.

- Visualize: Mentally walk through a "public hypo" scenario and see yourself handling it successfully.

A Personal Story: The Train Station Incident

I remember standing on a subway platform in London during rush hour. I felt that tell-tale cold sweat. My CGM buzzed: 55 mg/dL and dropping. My first instinct was embarrassment—I didn’t want to sit on the dirty floor in my suit. But the fog was rolling in fast.

I sat down right there, pulled out my glucose tabs, and started chewing. A woman stopped and asked if I was okay. Instead of saying "I'm fine" (the dangerous default), I said, "I'm having a diabetic low, I just need five minutes." She stood by me until I felt steady. That moment taught me that public vulnerability is actually a strength; it creates an opportunity for public awareness.

Boosting Public Awareness: How You Can Help

The general public often lacks a clear understanding of the difference between Type 1 and Type 2, or high and low blood sugar. We can bridge this gap by:

- Wearing Medical Jewelry: It starts conversations and provides vital info to first responders.

- Educating Your Circle: Ensure your friends, family, and coworkers know where your emergency kit is and how to use a glucagon pen.

- Sharing Your Story: Normalizing the use of insulin pumps and sensors in public helps reduce the stigma.