Explore the legal and ethical gray area of retro console emulation for game preservation

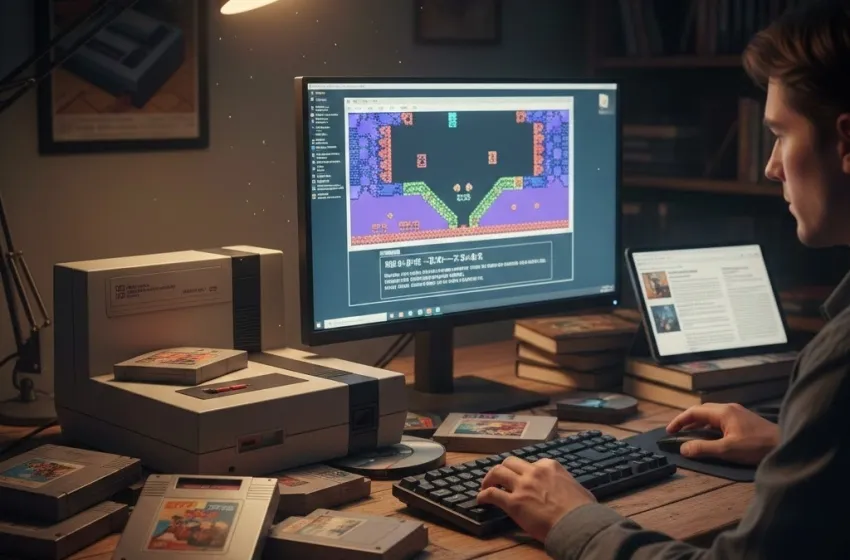

The siren song of retro console emulation is a powerful one, drawing in millions of enthusiasts driven by nostalgia for the blocky pixels and chiptune melodies of their youth. In an increasingly digital and ephemeral world, this practice—using software to mimic the hardware of older consoles—has become the primary method for experiencing classic video games. Yet, this entire ecosystem operates within a complex and highly contentious legal and ethical gray area, perpetually caught between the ideals of retro gaming preservation and the realities of intellectual property law.

To fully grasp the debate, one must first look at the history of consoles and the inherent fragility of their medium.

The Fragility of Gaming History

Video games are a relatively young art form, yet their earliest artifacts are already facing extinction. Unlike books or films, which can be preserved with comparative ease, video games are deeply intertwined with the proprietary, rapidly obsolescing hardware they were built for. Cartridges degrade, optical discs rot, and the specialized chips within classic consoles eventually fail. Furthermore, the commercial life of a console and its games is finite. Once a company decides a console is obsolete, manufacturing ceases, official repairs become impossible, and the games are pulled from digital rights platforms.

This is where the crisis of retro gaming preservation begins. When the original manufacturer no longer offers a game for sale—a state often referred to as "abandonware"—the only means of access for historians, researchers, and nostalgic fans alike often becomes the unauthorized, community-driven world of emulation.

The Legal Tightrope: Emulators vs. ROMs

The debate centers on two distinct, yet inextricably linked components: the emulator software and the game file (often called a ROM or ISO).

The Emulation Legality

In many jurisdictions, the act of creating and distributing an emulator program itself is generally considered legal. This stance is largely based on landmark U.S. court cases, notably Sony Computer Entertainment, Inc. v. Connectix Corporation (2000), which established that reverse-engineering proprietary hardware to achieve interoperability is protected under the Fair Use doctrine, provided the creator does not copy the original proprietary code, such as the console’s BIOS. An emulator is seen as an independently created piece of software designed to replicate the function of a console, not to duplicate it.

However, this legality has a massive caveat: the emulator is effectively a legal, empty vessel.

The Illegality of Distribution

The real legal danger lies in the distribution and download of the game files, or ROMs. These files are direct copies of the copyrighted game code, and their unauthorized distribution constitutes copyright infringement. Major companies, most notably Nintendo, have been aggressive in pursuing legal action against sites that host and distribute these copyrighted files. The argument from the copyright holder is simple: every unauthorized download is a lost sale, either of the original media or, more commonly today, a legally-licensed digital re-release on a modern platform.

Advocates for preservation, however, argue that this perspective ignores the reality of limited access. If a game is genuinely out-of-print, inaccessible, or only available at exorbitant collector prices, the economic harm to the copyright holder is negligible. For them, emulation becomes a necessity for cultural posterity.

Ethical Gray: Preservation, Nostalgia, and Limited Access

The ethical dimension of the debate is far murkier than the legal one, forcing players to confront their own sense of right and wrong, particularly concerning digital rights and corporate responsibility.

Limited Access and the Nostalgia Factor

For the average user, the appeal of emulation is deeply tied to nostalgia. They want to re-experience a cherished game without the hassle of locating working vintage hardware, managing unreliable media, and shelling out hundreds of dollars on the secondary market. When a game is only accessible through private collections or costly eBay auctions, the argument for piracy as an ethical means of consumption strengthens in the public eye.

Furthermore, many games were never officially released outside of a single region, locking them away from a global audience. The only way to play these games is through emulation, often enhanced by dedicated volunteers.

The Role of Fan Translation Patches

This is where the unique contribution of the emulation community becomes undeniable. Beyond simply replicating old games, the community actively improves them. Fan translation patches are a perfect example. These are community-made modifications that take a game released only in, say, Japanese, and translate the text and graphics into English or another language.

A famous example is Mother 3 for the Game Boy Advance. Nintendo never officially released this title in the West, citing the content as potentially controversial. A dedicated fan team spent years creating a highly professional and acclaimed translation patch. This preservation and enhancement effort adds immeasurable cultural value to a work that the original creators chose to abandon. Without emulation, this entire experience would be lost to the non-Japanese-speaking world. Ethically, the community often feels they are completing the work the company neglected.

The Corporate and Institutional Response

The traditional response from major copyright holders like Nintendo and Sony has been largely punitive, framing emulation as a threat to their digital rights and revenue stream. However, this stance is subtly shifting as companies realize the value of their back catalog.

Official Emulation and Re-release

Many major publishers now use official emulation solutions to re-release classic titles on modern consoles (e.g., Nintendo Switch Online, PlayStation Plus Classics, or virtual console services). This commercial approach validates the method of emulation as a viable form of distribution and preservation.

However, these official libraries are often curated, incomplete, and tethered to subscription services, meaning players don't own the game in a tangible sense. When a service shuts down, the digital license can vanish, creating a new layer of limited access—the "digital shelf-life" problem. This highlights a critical flaw in current digital rights models: they often prioritize temporary access over permanent ownership and preservation.

Institutional Archives

The conversation around retro gaming preservation is also shifting to formal institutions. Museums, libraries, and university archives are beginning to recognize video games as cultural heritage worthy of preservation. However, they face the same legal roadblocks. Current copyright law often restricts them from making the necessary digital copies for archival purposes or providing the public with access to the games via emulation, further underscoring the legal conundrum.

Looking Forward: A Call for Legal Clarity

The debate over retro console emulation is a microcosm of a larger societal struggle concerning digital rights in the 21st century. As culture becomes increasingly digital, the legal framework established for physical media struggles to keep pace.

Semantic keywords associated with this debate reinforce its multifaceted nature: copyright infringement, Fair Use doctrine, abandonware, ROM hacking, console piracy, hardware obsolescence, digital ownership, and cultural heritage. All of these terms circle back to the central tension: the need to preserve an important cultural artifact versus the right of the creator to control its distribution.

Ultimately, the resolution may require a legislative compromise. A clear, international legal framework is needed that establishes:

- Archival Exemption: Institutions should have explicit legal rights to use emulation to preserve and provide access to games that are no longer commercially available.

- Abandonware Distinction: A mechanism to legally define and release rights for games that the copyright holder has explicitly or implicitly abandoned.

- Community Contribution: Acknowledgment of fan contributions, such as fan translation patches, as non-profit, culturally beneficial works that should not be subject to automatic takedown, provided they are not commercialized.

Until such a framework is established, retro console emulation will continue to thrive in the ethical and legal shadows—a necessary, often illicit act of cultural rescue driven by the passionate belief that the history of consoles and their groundbreaking games is simply too valuable to be lost to time and decay. For millions of users, the ethical choice is clear: where companies fail to preserve, the community must step in, and nostalgia will forever remain the engine of preservation.