Learn the difference between COVID-19 lung inflammation and permanent pulmonary fibrosis, symptoms, and recovery options.

The 'Invisible Killer': Understanding Post-COVID Lung Scarring

The global pandemic may have transitioned into a manageable endemic phase, but for millions of survivors, the battle has moved from the intensive care unit to the respiratory clinic. Often referred to as the "invisible killer," post-viral damage in the form of lung scarring has emerged as one of the most daunting legacies of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

While many recover fully, a significant subset of patients continues to struggle with the long-term sequelae known as long COVID. Among the various manifestations of this condition, respiratory dysfunction—specifically pulmonary fibrosis—stands out as a critical concern for global health.

The High Incidence of Residual Lung Damage

Early in the pandemic, clinicians noticed that COVID-19 wasn't just a standard respiratory infection; it was a multi-system inflammatory event. Data now suggests that up to 30% of patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 show signs of residual lung abnormalities months after their initial "recovery."

In long COVID patients, the lungs often become the primary site of lingering symptoms. This isn't merely a feeling of being "out of shape." It is the physiological result of the body’s aggressive immune response to the virus. When the immune system overreacts, it triggers a cascade of viral inflammation that can fundamentally alter the architecture of the lung tissue.

Why the Lungs?

The SARS-CoV-2 virus enters the body through ACE2 receptors, which are particularly abundant in the type II alveolar cells of the lungs. These cells are responsible for producing surfactant and facilitating gas exchange. When these cells are destroyed, the body attempts to repair the damage. However, if the repair process goes awry, the result is fibrotic tissue—essentially internal scabs that don't breathe.

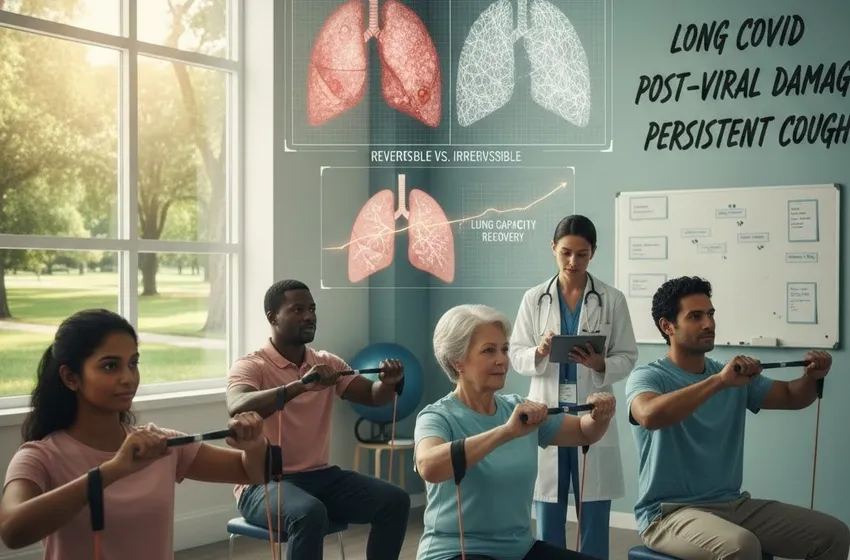

Reversible Inflammation vs. Irreversible Scarring

One of the most vital distinctions for patients to understand is the difference between pneumonitis (inflammation) and fibrosis (scarring).

1. Reversible Inflammation

In the weeks following a COVID-19 infection, many patients experience a persistent cough and shortness of breath. Often, this is caused by lingering viral inflammation. The lung tissue is swollen and congested, but the underlying structure remains intact. With time, steroids, or pulmonary rehabilitation, this inflammation can subside, allowing the lungs to return to their normal state.

2. Irreversible Scarring (Pulmonary Fibrosis)

If the inflammatory phase is too intense or lasts too long, the body begins to replace delicate lung tissue with thick, inelastic connective tissue. This is pulmonary fibrosis. Unlike inflammation, scarring is permanent. Scarred tissue is stiff, making it difficult for the lungs to expand and harder for oxygen to enter the bloodstream.

Key Takeaway: Early intervention is critical. The goal of post-COVID care is to "cool down" the inflammation before it hardens into permanent scars.

Navigating Lung Capacity Recovery

For those diagnosed with post-COVID lung damage, the road to lung capacity recovery is rarely a straight line. It requires a multidisciplinary approach involving pulmonologists, physical therapists, and nutritionists.

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Specialized exercise programs designed to retrain the lungs and the muscles used for breathing.

- Breathing Techniques: Diaphragmatic breathing helps maximize the oxygen intake of the remaining healthy lung tissue.

- Anti-fibrotic Medications: In some severe cases, drugs originally designed for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are used to slow the progression of COVID-related scarring.

The Symptoms You Shouldn't Ignore

While a persistent cough is common after any viral flu, in the context of long COVID, it can be a red flag for underlying post-viral damage. Patients should seek medical advice if they experience:

- Shortness of breath during low-impact activities.

- A "dry," hacking cough that lasts longer than 8 weeks.

- Chest tightness or chronic fatigue that doesn't improve with rest.

Summary of Clinical Outlook

The "Invisible Killer" slowly diminishes the quality of life through pulmonary fibrosis. However, by focusing on early detection of post-viral damage and dedicated lung capacity recovery programs, we can help survivors breathe easier.