Explore the evolution of Infrastructure as Code (IaC)

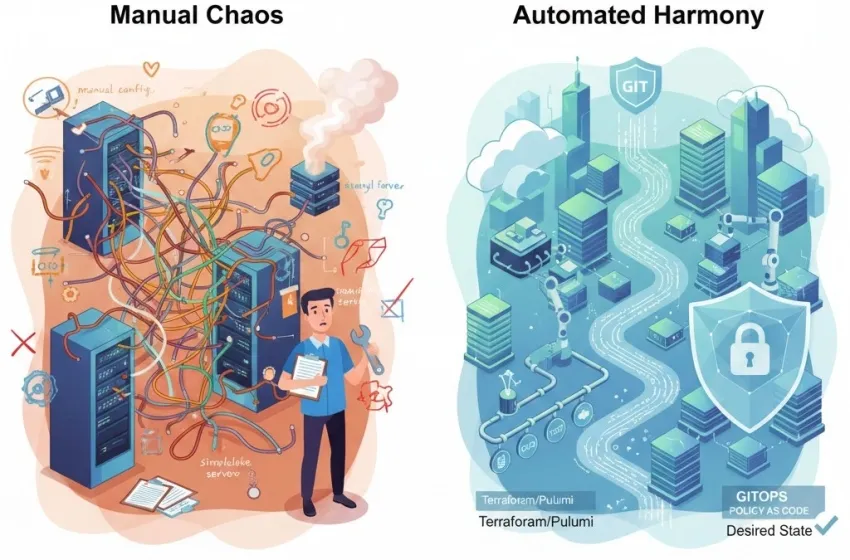

The modern digital landscape is defined by speed, scale, and resilience. At the core of achieving this lies a foundational principle of the DevOps movement: Infrastructure as Code (IaC). More than a mere trend, IaC represents a revolutionary shift in how organizations manage and provision their technology infrastructure, treating it with the same discipline and rigor as application source code. This evolution has transformed a process once characterized by manual, error-prone, and time-consuming tasks into an automated, repeatable, and verifiable system.

This comprehensive guide delves into the historical context, core principles, technical evolution, and future trajectory of IaC, highlighting how it enables the managing and provisioning technology infrastructure through code, ensuring reproducibility and version control for cloud resources.

The Genesis of IaC: From Shell Scripts to Desired State

The need for IaC was born out of the pain points of the pre-cloud era, where infrastructure management was an artisanal process.

The Era of "Snowflakes" and Manual Pain

Before the advent of widespread cloud computing and sophisticated automation, provisioning servers, configuring networks, and managing databases were primarily manual processes. System administrators would log into machines, execute shell scripts, and manually configure operating systems, middleware, and applications.

This manual, imperative approach led to a phenomenon known as "snowflake servers"—unique, non-reproducible configurations where each server had its own subtle, often undocumented, variations. While one server might be working perfectly, an identical one provisioned manually later could fail due to a missed step or a minor version difference. This lack of reproducibility was the primary bottleneck to speed, reliability, and scale.

The Dawn of Configuration Management

The first major evolutionary leap occurred with the emergence of powerful configuration management tools in the early to mid-2000s, such as CFEngine, and later Puppet, Chef, and Ansible. These tools introduced the pivotal concept of desired state configuration.

The desired state configuration model flipped the script from the imperative approach (specifying how to achieve a configuration) to a declarative infrastructure approach (specifying what the final configuration should look like). The tool’s agent or orchestrator was responsible for reconciling the current state of the infrastructure with the defined desired state, applying changes as needed. This was a critical step in the evolution:

- Idempotency: The process could be run repeatedly, ensuring the infrastructure reached the same end state every time, regardless of the starting condition.

- Consistency: The configuration definition became a single source of truth, drastically reducing manual errors and the proliferation of "snowflake" environments.

The Cloud Revolution and the Rise of Declarative Provisioning

The move to cloud environments (AWS, Azure, GCP) fundamentally changed the infrastructure provisioning landscape. Infrastructure became a programmable, API-driven utility, paving the way for the second major evolution of IaC: resource provisioning.

Separating Provisioning and Configuration

Early IaC solutions primarily focused on configuration—the setup inside a server (e.g., packages, users, services). The cloud era demanded a focus on provisioning—the creation of the resources themselves (e.g., Virtual Machines, Virtual Private Clouds, Load Balancers).

Cloud providers developed their own proprietary IaC tools, such as AWS CloudFormation and Azure Resource Manager (ARM), which used declarative infrastructure to define complex stacks of cloud services. These tools codified the entire data center architecture, from networking to compute to security policies.

The Cross-Cloud Standard: Terraform/Pulumi

As organizations adopted multi-cloud strategies, a need for a unified, cloud-agnostic IaC tool became apparent. This led to the rise of multi-cloud IaC platforms, primarily Terraform/Pulumi.

- Terraform (using HashiCorp Configuration Language or HCL) and Pulumi (allowing the use of general-purpose languages like Python, Go, and TypeScript) cemented the declarative infrastructure paradigm.

- These tools manage the full lifecycle of resources—creation, updates, and deletion—by maintaining a state file that maps the code definition to the real-world resources.

The use of Terraform/Pulumi elevated IaC beyond just server configuration to encompass all public cloud, private cloud, and SaaS infrastructure components, making them the industry standard for cloud resource provisioning.

By leveraging a declarative infrastructure approach, teams can define their required cloud resources and allow the tool's engine to calculate the execution plan, minimizing human error and providing a clear preview of changes before they are applied.

The Challenge of Configuration Drift

Despite the move to desired state configuration and declarative infrastructure, a persistent problem remained: configuration drift.

Configuration drift occurs when the actual state of a running infrastructure resource deviates from its state definition in the IaC code. This usually happens when:

- Manual Intervention: An operator makes an urgent change directly in the cloud console without updating the IaC code.

- Tool-Specific Issues: A non-idempotent script or a configuration management tool makes an ad-hoc change that the provisioning tool (like Terraform) doesn't track.

Configuration drift is a major threat to reproducibility, security, and compliance. If a server is manually patched in production but not in the IaC definition, the next automated deployment or environment rebuild will revert the change, potentially causing an outage or a security vulnerability.

The solution to this problem required integrating IaC not just as a deployment mechanism, but as a continuous operational control system.

The New Frontier: GitOps and Continuous Reconciliation

The latest and arguably most impactful evolution of IaC is the adoption of GitOps. GitOps is an operational framework that takes DevOps best practices, like version control and CI/CD, and applies them directly to infrastructure automation, fundamentally addressing the configuration drift problem.

Git as the Single Source of Truth

At its core, GitOps mandates that Git is the single source of truth for both application and declarative infrastructure definitions. Every change to the infrastructure—from provisioning a new VM to configuring a Kubernetes deployment—must start with a pull request to the infrastructure repository.

This introduces a robust, auditable workflow:

- Version Control and Audit: All infrastructure changes are tracked via Git, providing a complete, cryptographically verified history of who, what, and when. This is key for compliance and rapid rollback.

- Peer Review: Changes are reviewed by team members before merging, improving quality and catching errors early.

- CI/CD Pipeline: The merge automatically triggers an automated pipeline to plan, test, and apply the infrastructure changes.

Continuous Reconciliation and the GitOps Agent

The true innovation of GitOps is the introduction of a specialized agent (like Argo CD or Flux) that runs inside the infrastructure (typically Kubernetes) and continuously monitors the system.

- The agent constantly compares the desired state configuration defined in the Git repository with the actual, live state of the cluster.

- If the agent detects a difference—which is exactly what configuration drift is—it automatically attempts to reconcile the live state to match the code in Git.

This mechanism makes configuration drift impossible to sustain for long, as the system self-heals by enforcing the declarative infrastructure definition. This continuous, pull-based deployment model is transforming how organizations manage their cloud-native infrastructure, making it more resilient, auditable, and inherently reproducible.

The Future of IaC: Policy, Intelligence, and Language

The journey of Infrastructure as Code (IaC) is far from over. The future is being shaped by advancements in governance, abstraction, and AI-driven intelligence.

Policy as Code (PaC) and Governance

As IaC enables greater speed, it also requires tighter controls. Policy as Code (PaC) is the next logical step, where security, compliance, and cost policies are defined, stored in Git, and enforced before infrastructure is provisioned. Tools like Open Policy Agent (OPA) integrate with platforms like Terraform/Pulumi to prevent the deployment of non-compliant resources, such as creating an S3 bucket without encryption enabled. This shift moves security and governance "left" into the developer workflow.

High-Level Abstractions

While HCL and YAML are powerful, the industry is moving towards even higher levels of abstraction. Tools like the AWS Cloud Development Kit (CDK) and Pulumi (with its use of programming languages) allow engineers to define infrastructure using familiar software development paradigms. This makes IaC more accessible to developers and allows for greater reuse through object-oriented constructs, accelerating the creation of complex, modular, and declarative infrastructure.

AI and Autonomous Infrastructure Management

The ultimate evolution envisions a degree of autonomous infrastructure. AI/ML models, trained on historical infrastructure data and cost/performance metrics, could one day propose and even execute infrastructure changes via IaC, optimizing for efficiency and resilience while still adhering to the GitOps principles of code-review and audibility.

Summary of the IaC Journey

The evolution of Infrastructure as Code (IaC) is a narrative of moving from manual, low-level control to highly automated, high-level declarations:

| Stage | Goal | Key Approach | Key Tool/Concept | Solved Pain Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Early Automation | Configuration Management | Imperative/Procedural Scripts | Shell Scripts, CFEngine | Time-Consuming Manual Steps |

| II. Desired State | Consistent Server Configuration | Desired State Configuration | Chef, Puppet, Ansible | Configuration Drift, Snowflake Servers |

| III. Cloud Provisioning | Full Cloud Stack Provisioning | Declarative Infrastructure | CloudFormation, Terraform/Pulumi | Lack of Reproducibility for Cloud Resources |

| IV. Continuous Automation | Operational Enforcement | GitOps (Pull-Based) | Argo CD, Flux | Unmanaged Configuration Drift in Production |

By embracing Infrastructure as Code (IaC) and its mature frameworks like GitOps, organizations are not just automating tasks; they are institutionalizing the principles of consistency, auditability, and speed, making their technology stacks robust and future-proof. Terraform/Pulumi have become essential tools in this landscape, enabling teams to define their declarative infrastructure and maintain a verifiable, single source of truth for their entire environment.