Learn the difference between heart failure and heart attacks.

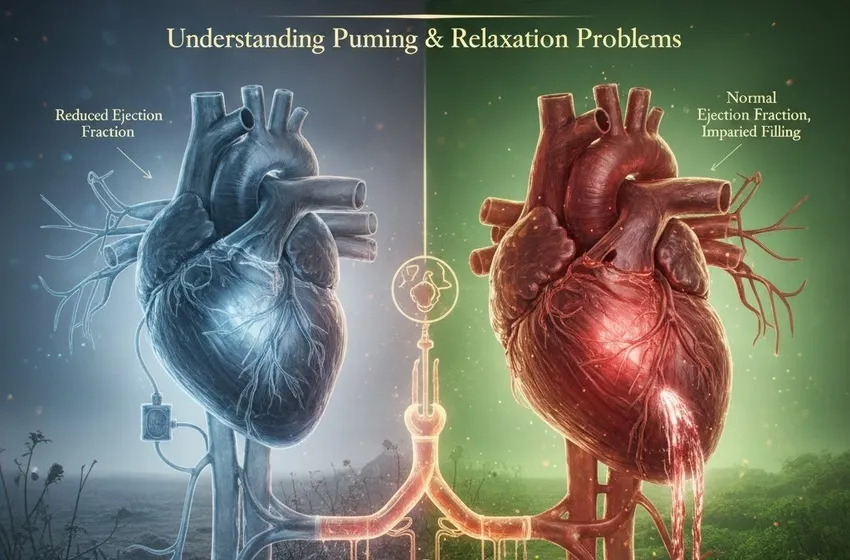

Heart Failure: Understanding Pumping & Relaxation Problems

Heart failure is one of the most misunderstood terms in medicine. For many, the phrase sounds like a sudden, final event where the heart simply stops beating. In reality, heart failure is a chronic, progressive condition where the heart muscle struggles to meet the body's demands for blood and oxygen. It is a journey of management, not an immediate "failure" of life.

Clarifying the Difference: Heart Failure vs. Heart Attack

It is essential to start by clarifying that heart failure is not the same as a heart attack. While they are both serious cardiovascular conditions, their "mechanisms" are entirely different:

- A Heart Attack (Myocardial Infarction): This is a "plumbing" problem. It occurs when a blockage in a coronary artery suddenly cuts off blood flow to a portion of the heart muscle. Without oxygen, that part of the muscle begins to die.

- Heart Failure: This is a "pumping" or "structural" problem. It occurs over time as the heart becomes too weak or too stiff to circulate blood effectively.

While a heart attack can cause the muscle damage that eventually leads to heart failure, they are distinct diagnoses. You can have heart failure without ever having a heart attack, and many people survive heart attacks without developing heart failure.

The Two Faces of Left-Sided Heart Failure

Most heart failure begins on the left side. The left ventricle is the heart's "powerhouse," responsible for pumping oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body. When we discuss left-sided heart failure, we generally categorize it into two distinct types based on how the heart is failing to do its job.

1. Pumping Problems: Systolic Heart Failure

In systolic heart failure, the heart muscle becomes thin and weak. It loses its ability to contract with enough force to push blood into the circulation.

A critical measurement used here is the ejection fraction (EF). This is a percentage that represents how much blood the left ventricle pumps out with each contraction. A normal EF is typically between 50% and 70%. In systolic heart failure—also known as Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF)—the ejection fraction often drops below 40%. Because the "pump" is weak, the body doesn't receive the oxygen it needs to function at full capacity.

2. Relaxation Problems: Diastolic Heart Failure

Interestingly, the heart can have a normal ejection fraction and still be in failure. This is called diastolic heart failure, or Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF).

In this scenario, the heart muscle is not weak; instead, it has become thick and stiff. Because the muscle cannot relax properly between beats, the chamber cannot fill with enough blood. If the heart doesn't fill up, it doesn't matter how strong the pump is—there simply isn't enough blood to go around. This "relaxation problem" is just as serious as a "pumping problem" and often affects older adults or those with long-term high blood pressure.

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) and Fluid Dynamics

When the heart cannot pump or fill efficiently, blood begins to "back up" in the system, much like a traffic jam on a highway. This backup increases pressure in the blood vessels, eventually forcing fluid out of the vessels and into the surrounding tissues. This stage is often called congestive heart failure (CHF).

The Impact of Fluid Buildup

The primary hallmark of congestive heart failure (CHF) is fluid buildup. Depending on where the fluid settles, the symptoms change:

- Lungs: When fluid backs up into the lungs, it leads to pulmonary congestion. This causes a hallmark symptom: shortness of breath (dyspnea). You might notice this during physical activity, but in more advanced stages, it can occur while you are resting or trying to sleep flat at night.

- Lower Extremities: Gravity often pulls excess fluid toward the feet and ankles, leading to edema (swelling). You might notice your shoes feel tighter or that pressing your finger into your shin leaves a temporary "pit" or indentation.

- Abdomen: Fluid can also collect in the belly, causing bloating, a feeling of fullness, or even loss of appetite.

Recognizing the Symptoms of Fluid Retention

Because heart failure is a chronic condition, "episodes" or flare-ups are often triggered by a sudden increase in fluid buildup. Monitoring these symptoms daily is a vital part of self-care.

| Symptom | What it Feels Like | Why it Happens |

|---|---|---|

| Shortness of breath (dyspnea) | Difficulty breathing during simple tasks or when lying down. | Fluid in the air sacs of the lungs makes it hard to exchange oxygen. |

| Pitting Edema | Swelling in the legs, ankles, or feet. | Increased venous pressure forces water into the tissues. |

| Orthopnea | Needing to prop yourself up with pillows to breathe while sleeping. | Lying flat allows fluid to spread across the lungs; staying upright keeps it at the base. |

| Rapid Weight Gain | Gaining 2–3 pounds in a day or 5 pounds in a week. | This is almost always "water weight" rather than fat, signaling a need for medical adjustment. |

Treatment Goals: Strengthening the Pump and Relieving the Pressure

While heart failure is usually a lifelong condition, the treatment goals are clear: improve quality of life, reduce hospitalizations, and help the heart work more efficiently.

1. Removing Excess Fluid

The most immediate goal is often relieving the "congestion." Doctors frequently prescribe diuretics (water pills) to help the kidneys flush out extra salt and water. This reduces edema and eases the workload on the heart.

2. Neurohormonal Blockade

When the heart fails, the body releases "stress hormones" (like adrenaline) to try and force the heart to beat faster. While this helps in the short term, it damages the heart over time. Medications like Beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors are used to block these harmful signals, allowing the heart muscle to rest and, in some cases, even improve its ejection fraction over time.

3. Lifestyle Modification

Treatment isn't just about pills. Managing congestive heart failure (CHF) requires a partnership between the patient and the medical team. Key lifestyle goals include:

- Sodium Restriction: Salt acts like a sponge, holding onto water. Lowering salt intake is essential to preventing fluid retention.

- Fluid Monitoring: In some cases, patients must limit their daily fluid intake to prevent the system from becoming overloaded.

- Exercise: Cardiac rehabilitation can help the body’s muscles become more efficient at using oxygen, taking some of the pressure off the heart.

Conclusion

Understanding the difference between pumping and relaxation problems is the first step in managing heart failure. Whether you are dealing with a reduced ejection fraction or a stiff heart, the goal remains the same: balance the fluids, support the muscle, and stay vigilant against shortness of breath (dyspnea) and edema. With modern medicine and dedicated self-care, many people with heart failure continue to lead active, fulfilling lives.