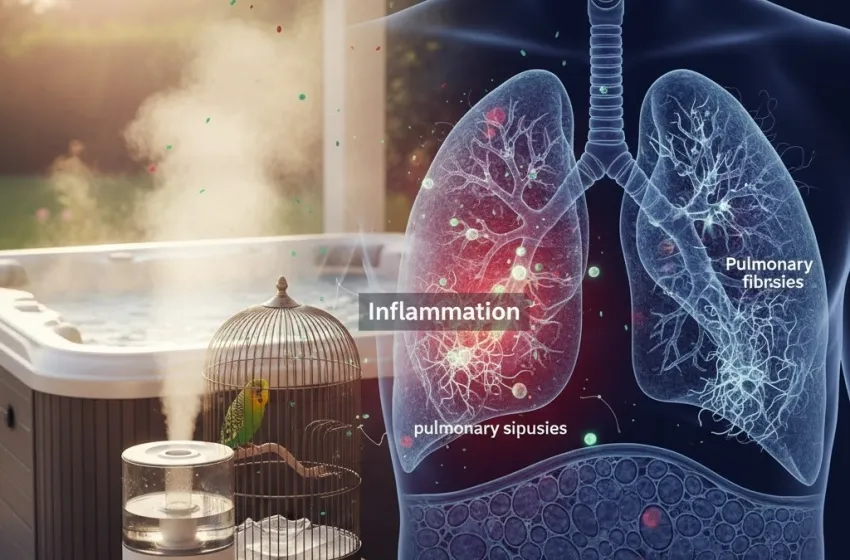

Learn about organic dust exposure and lung inflammation.

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis (HSP), also known as Extrinsic Allergic Alveolitis (EAA), is a complex and often insidious lung disease that results from an immunological reaction to inhaled environmental antigens. While historically viewed as a rare, occupational exposure illness tied primarily to farming and specific industries, its prevalence is demonstrably on the rise. This increase is driven not just by a genuine proliferation of antigenic sources in modern life—from contaminated household water systems to common pets—but also by a growing awareness among clinicians that this condition is frequently overlooked, often lurking behind misdiagnoses of more common respiratory ailments like asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), or even Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF).

The true challenge of HSP lies in its multifaceted presentation, which can range from acute, flu-like symptoms to a slow, debilitating fibrotic process. For patients, delayed diagnosis can be the difference between a reversible lung injury and progressive, irreversible pulmonary fibrosis. For the healthcare system, the rise of HSP represents a quiet epidemic, demanding a fundamental shift in diagnostic protocols and environmental awareness.

Defining the Disease: Antigen-Driven Lung Inflammation

At its core, Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis is an inflammatory disorder of the lung parenchyma—specifically the small airways (bronchioles) and the air sacs (alveoli)—triggered by a hypersensitivity immune response. It is not a classic allergy like hay fever, but rather a more delayed and profound immune reaction, typically involving a combination of Type III (immune complex deposition) and Type IV (T-cell-mediated) hypersensitivity.

When a susceptible individual inhales a sufficiently small antigen (usually less than $5 \mu \text{m}$ in diameter) that can reach the deep recesses of the lung, the immune system launches an aggressive defense. This response results in profound inflammation and the formation of characteristic, poorly formed granulomas in the lung tissue.

The disease is classically categorized into three forms, which often blur in clinical practice:

- Acute HP: Occurs hours after a high-intensity exposure, presenting with flu-like symptoms (fever, chills, body aches, cough, and shortness of breath) that typically resolve within days if the antigen is avoided.

- Subacute HP: Characterized by more insidious symptoms—cough, progressive shortness of breath, and fatigue—developing over weeks or months from repeated, lower-level exposures.

- Chronic HP: Develops over months to years from sustained exposure, leading to progressive scarring (fibrosis) of the lung tissue. This is the most dangerous form, carrying a significantly worse prognosis.

The Escalating Incidence: A Modern Environmental Threat

While some of the observed increase in HSP cases may be attributed to a growing recognition of the disease (improved HRCT imaging, better diagnostic criteria), compelling evidence suggests a genuine rise tied to the modernization of our indoor and occupational exposure environments.

The list of causative antigens now exceeds 300, but a common thread ties many of the newer, domestically-acquired cases: moisture and microbial growth. Modern, energy-efficient building designs, which often reduce airflow, inadvertently create ideal environments for the proliferation of molds, bacteria, and thermophilic actinomycetes—the key culprits in many hypersensitivity reactions.

Hot Tubs, Humidifiers, and Household Air

The rise of certain domestic forms of HSP provides a stark illustration of this modern environmental shift.

One of the most recognized of these syndromes is hot tub lung. This distinct form of HSP is typically caused not by chlorine or chemical irritants, but by the aerosolization of Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), a type of non-tuberculous mycobacteria that thrives in the warm, stagnant water and moist air of improperly maintained hot tubs, spas, and indoor swimming pools. When the water is jetted, the MAC bacteria are inhaled deep into the lungs, triggering a profound, delayed immune reaction. Unlike the standard HSP driven by mold spores or bird antigens, hot tub lung often presents with a unique constellation of symptoms and radiological findings, making it a critical entity to distinguish.

Similarly, contaminated humidifiers, heating, and air conditioning systems are notorious sources, often leading to "Humidifier Lung." Any device that creates a fine water mist from a reservoir can become a breeding ground for bacteria or fungi, which are then distributed as a breathable bioaerosol throughout a home or office. As more people use such devices for comfort, the risk of developing these hypersensitivity reactions increases proportionally.

Bird Fancier's Lung and the Domestic Pet Boom

Beyond water sources, the increase in pet ownership—particularly birds—has amplified the risk of bird fancier's lung (BFL), arguably the most common and best-studied form of HSP worldwide. BFL is triggered by inhaling organic dust exposure containing avian proteins found in feathers, feather dust, and dried droppings from species like pigeons, parakeets, and chickens.

Crucially, exposure is not limited to bird breeders or zookeepers. Simple household exposure to a pet bird, or even the antigens contained in feather-filled duvets, down comforters, or pillows, can be sufficient to trigger the syndrome in a susceptible person. The subtle, constant low-level exposure from a household pet makes BFL a prime candidate for chronic, insidious progression, as the patient is rarely aware of the true culprit until the damage is already significant.

The Challenge of Misdiagnosis: Addressing the Increase

Addressing the increase in hypersensitivity reactions from common sources like humidifiers, hot tubs, and even pet birds, often misdiagnosed as other conditions is arguably the most urgent clinical necessity. The non-specific nature of HSP symptoms is the root of this diagnostic pitfall.

- Acute HP vs. The Flu/Bronchitis: Acute HSP is often dismissed as a severe flu or acute bronchitis because of its presentation: fever, chills, cough, and myalgias developing a few hours after exposure. A patient may receive antibiotics or flu-specific treatment, fail to improve, and continue exposure to the antigen, pushing the disease toward a chronic state.

- Chronic HP vs. Asthma/COPD: The long-term presentation of chronic HSP—progressive shortness of breath, chronic cough, and fatigue—is often confused with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) or refractory asthma. The patient may be treated with inhalers that fail to address the underlying immune-mediated inflammation and fibrosis.

- Chronic Fibrotic HP vs. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF): This misdiagnosis is the most critical. Chronic HSP that has progressed to fibrosis can look almost identical to IPF on clinical presentation and basic imaging. Historically, patients with fibrotic HSP were often lumped into the IPF category—a disease with a grim, untreatable prognosis.

The key to distinguishing HSP from these other conditions is a rigorous, detailed exposure history. Questions about home water systems (humidifiers, hot tubs), pets (bird fancier's lung), hobbies (composting, woodworking), and a detailed occupational exposure survey are essential.

Pathogenesis and Prognosis: Reversible vs Chronic Damage

The difference between a good prognosis and a life-limiting diagnosis in HSP hinges on the stage of the disease and the extent of fibrosis. This is the distinction between reversible vs chronic damage.

In the acute and subacute phases, the damage is primarily characterized by lymphocytic and granulomatous inflammation. If the offending antigen is identified and completely avoided—a process known as antigen avoidance—the inflammation can often be fully or largely reversed. The lungs can heal, and normal function can be restored.

However, repeated or prolonged exposure to organic dust exposure and other antigens pushes the disease process past this point. The persistent inflammation leads to a cascade of events that remodels the lung structure:

- Chronic Damage and Fibrosis: Chronic HSP leads to interstitial lung disease (ILD), characterized by the deposition of excess collagen, which results in irreversible scarring, or pulmonary fibrosis. The lung tissue becomes stiff and thick, losing its ability to efficiently exchange oxygen.

- Irreversible Decline: Once significant pulmonary fibrosis has set in, the damage is largely chronic damage and cannot be reversed by simply avoiding the antigen. The patient is often left with permanent respiratory impairment, which can progress to respiratory failure.

Treatment in the chronic fibrotic stage shifts from simply stopping the exposure to aggressive immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., corticosteroids) to halt the progression of inflammation and, more recently, the use of anti-fibrotic medications originally developed for IPF. Early diagnosis and timely antigen avoidance, therefore, remain the cornerstone of effective management.

Mitigating the Risk and Moving Forward

The rise of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis calls for a multi-pronged public health and clinical response focused on education and prevention.

Domestic and Environmental Prevention

- Water System Maintenance: Strict, regular cleaning and maintenance of any device that aerosolizes water—humidifiers, nebulizers, air conditioners, and especially hot tubs lung systems—is paramount to prevent the growth of MAC and molds.

- Pet Management: For bird owners, scrupulous hygiene, regular cage cleaning (ideally by a non-sensitized individual), and the use of air filtration can reduce the antigen burden responsible for bird fancier's lung. For susceptible individuals, feather-filled bedding should be replaced with synthetic alternatives.

- Mold Remediation: Addressing water leaks, damp basements, and visible mold growth in homes is a direct measure against organic dust exposure.

Clinical and Occupational Exposure Strategy

- High Index of Suspicion: Clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for HSP in any patient with chronic or recurring respiratory symptoms, regardless of their work history.

- Detailed History: A specialized, detailed exposure questionnaire must become standard practice for all new interstitial lung disease or refractory asthma patients.

- Industrial Hygiene: In traditional occupational exposure settings—such as farming (Farmer’s Lung), mushroom cultivation (Mushroom Worker’s Lung), or metalworking (Metalworker’s Lung)—proper engineering controls, ventilation systems, and mandatory use of appropriate respiratory Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) are essential to minimize dust and bioaerosol inhalation.

By recognizing the increasingly ubiquitous nature of the antigens responsible for HSP—from the backyard hot tub lung to the bird fancier's lung in the living room—and by embracing the diagnostic rigor needed to move past common misdiagnoses, the medical community can better manage this hidden epidemic and limit the devastating impact of chronic damage and fibrosis on patients' lives.