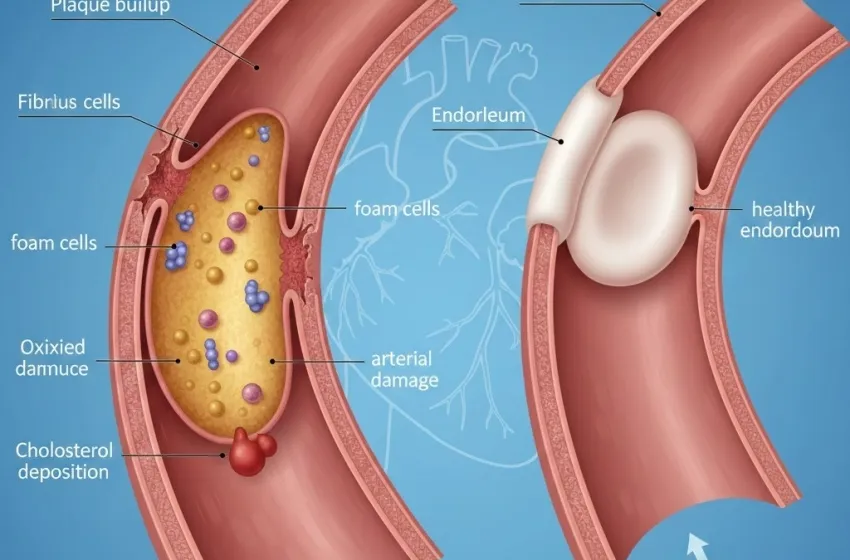

Learn how plaque buildup and hardening of arteries occur, from arterial damage to cholesterol deposition.

Atherosclerosis is a chronic, progressive disease affecting the arterial walls, often referred to as the hardening of arteries. It's the primary underlying cause of most cardiovascular diseases, including heart attacks and strokes, making its understanding and management vital for long-term health. This condition begins silently, often in early adulthood, characterized by plaque buildup within the innermost lining of the arteries.

The Mechanism of Atherosclerosis: From Damage to Plaque

Atherosclerosis is fundamentally an inflammatory response to injury within the arterial wall. The process is complex but generally follows several key stages:

Endothelial Dysfunction and Arterial Damage

The process initiates with injury to the healthy endothelium, the delicate, single-cell layer lining the inside of all blood vessels. This layer, when healthy, acts as a protective barrier, preventing blood components from adhering to the vessel wall and releasing molecules that regulate blood vessel tone. However, factors like high blood pressure (hypertension), elevated levels of "bad" cholesterol (low-density lipoprotein or LDL), smoking, diabetes, and other atherosclerosis causes lead to oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, damaging the endothelium. This damage makes the endothelial lining more permeable and "sticky."

Cholesterol Deposition and LDL Infiltration

Once the endothelium is compromised, circulating LDL cholesterol particles, particularly those that have been oxidized (a key step in their pathogenicity), infiltrate the sub-endothelial space (the layer just beneath the endothelium). This infiltration is known as cholesterol deposition. The LDL particles accumulate and become trapped within the arterial wall.

Macrophage Recruitment and Foam Cell Formation

The immune system recognizes these trapped, modified LDL particles as foreign invaders and initiates an inflammatory response. Monocytes, a type of white blood cell, are recruited from the bloodstream into the arterial wall, where they transform into large, voracious cells called macrophages. These macrophages avidly engulf the modified LDL cholesterol in an attempt to clear it. As they gorge on cholesterol, they swell up and transform into characteristic foam cells, which are the earliest cellular components of the atherosclerotic lesion, or fatty streak.

Plaque Formation and Fibrous Cap Development

The continued accumulation of foam cells, smooth muscle cells, cellular debris, and extracellular lipids leads to the formation of a raised lesion called an atherosclerotic plaque. Over time, smooth muscle cells migrate from the middle layer of the artery (media) to the intimal layer (innermost layer) and proliferate. They produce a fibrous matrix, primarily collagen, that forms a fibrous cap over the soft, lipid-rich core of the plaque.

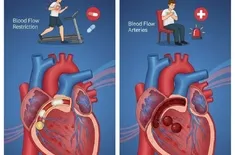

Clinical Sequelae: Stenosis and Thrombosis

This progressive plaque buildup narrows the arterial lumen, a condition called stenosis, restricting blood flow and oxygen supply to downstream tissues. This is the cause of symptoms like angina (chest pain). More dangerously, the stability of the plaque is key. If the fibrous cap is thin, inflamed, and ruptures, the contents of the highly thrombogenic (clot-forming) lipid core are exposed to the bloodstream. This immediately triggers the coagulation cascade, forming a blood clot (thrombus) that can rapidly occlude the vessel, leading to an acute event: a myocardial infarction (heart attack) if it occurs in the coronary arteries, or an ischemic stroke if in the cerebral arteries.

Actionable Steps to Slow or Potentially Reverse Atherosclerosis

While the condition is chronic, evidence suggests that aggressive management of risk factors can not only halt the progression of plaque buildup but, in some cases, induce *plaque regression* or stabilization, significantly reducing the risk of cardiovascular events.

A. Comprehensive Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle changes are the cornerstone of both prevention and reversal. They directly address the primary atherosclerosis causes.

Dietary Interventions (The "Heart-Healthy" Diet):

- Focus on Whole Foods: Adopt a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes. Diets like the Mediterranean Diet or DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) are highly effective.

- Reduce Saturated and Trans Fats: Limiting these fats is crucial for lowering LDL cholesterol and reducing cholesterol deposition. Focus instead on healthy monounsaturated fats (olives, avocados, nuts) and polyunsaturated fats (fatty fish like salmon, providing Omega-3 fatty acids).

- Increase Fiber Intake: Soluble fiber (oats, beans, apples) binds with cholesterol in the digestive system, preventing its absorption and aiding in LDL reduction.

- Limit Sodium and Sugar: Reducing salt intake helps manage high blood pressure, while cutting back on refined sugars and simple carbohydrates can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce inflammation.

Regular Physical Activity:

Aim for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (e.g., brisk walking) or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise. Exercise helps raise protective HDL cholesterol, lowers blood pressure, improves blood sugar control, and helps maintain a healthy endothelium.

Smoking Cessation:

Smoking is one of the most potent triggers of arterial damage. Quitting smoking is arguably the single most impactful action one can take to slow or reverse the process. The benefits are seen almost immediately.

Weight Management:

Achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight (BMI between 18.5 and 24.9) reduces the burden on the cardiovascular system and improves lipid and glucose metabolism.

Stress Reduction and Sleep Hygiene:

Chronic stress elevates cortisol and blood pressure, contributing to arterial damage. Techniques like mindfulness, yoga, and ensuring 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night are essential.

B. Pharmacological Management

Medication is often necessary, especially for individuals with established disease or multiple high-risk factors, to aggressively lower lipid levels and control blood pressure.

| Medication Class | Primary Mechanism of Action | Role in Reversing Atherosclerosis |

|---|---|---|

| Statins (HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors) | Reduce the liver's production of cholesterol. They are highly effective at lowering LDL cholesterol. | The most potent and well-studied class for plaque stabilization and regression. High-intensity Statins can reduce the volume of plaque buildup and heal the fibrous cap, reducing the risk of rupture. They also have pleiotropic (anti-inflammatory) effects. |

| PCSK9 Inhibitors | Block a protein (PCSK9) that degrades LDL receptors on liver cells, leading to a dramatic increase in LDL removal from the blood. | Used for very high-risk patients or those who cannot tolerate statins. They provide a massive reduction in LDL and can accelerate plaque regression. |

| Aspirin / Antiplatelets | Prevent platelets from clumping together, reducing the likelihood of a blood clot forming after a plaque rupture. | Primarily for secondary prevention (after an event) or high-risk primary prevention. It doesn't reverse plaque but prevents the lethal complications (thrombosis). |

| ACE Inhibitors / ARBs | Lower blood pressure and reduce the remodeling of the heart and blood vessels. | Essential for treating hypertension, which is a major contributor to arterial damage and atherosclerosis causes. |

The goal of medication, particularly with Statins and PCSK9 inhibitors, is to drive LDL cholesterol levels down significantly (often to levels below 70 mg/dL or even lower for very high-risk patients). This aggressive reduction creates a steep concentration gradient, effectively pulling cholesterol out of the arterial wall and facilitating plaque regression and healing of the healthy endothelium.